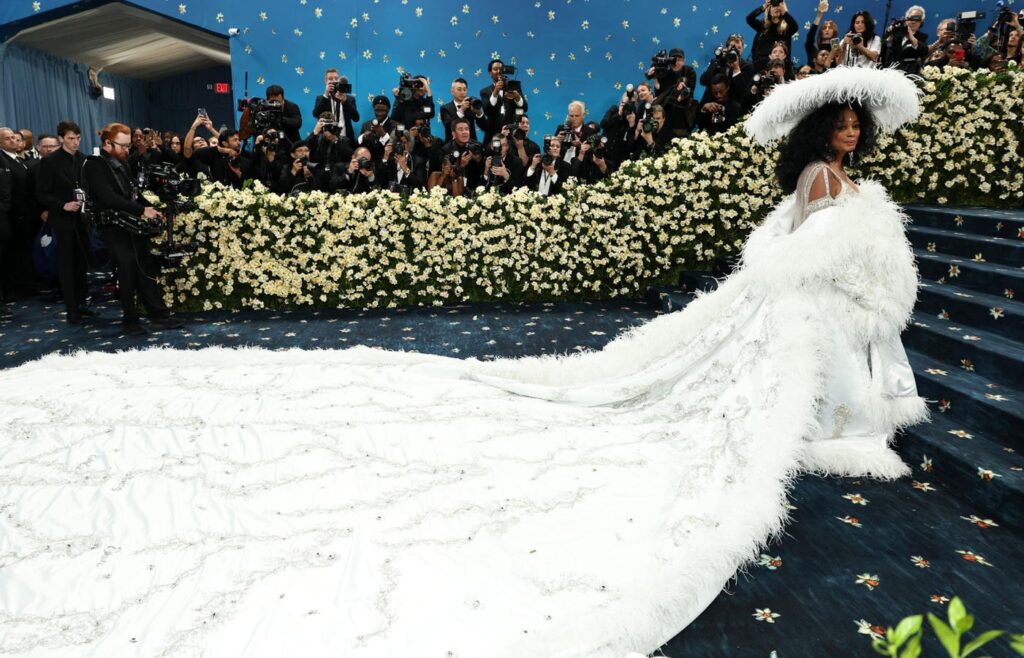

When New York Times columnist Binyamin Appelbaum questioned the fairness of charitable deductions—using the $75,000 Met Gala ticket as an example of tax-subsidized elite indulgence—he tapped into a cultural controversy. However, his argument reveals a critical misunderstanding, especially relevant for financial advisors, estate planners, and philanthropists.

Appelbaum argues that charitable deductions disproportionately benefit wealthy donors and elite institutions such as museums and universities rather than grassroots charities. He suggests replacing these deductions with flat tax credits or matching grants to equalize government support. While emotionally appealing, this critique contains a logical fallacy: it confuses who benefits from the deduction with the deduction’s intended purpose.

Charitable Deductions Are Not Government Grants to the Wealthy

A charitable deduction is not an institutional subsidy: it is a one-for-one reduction in the donor’s taxable income. By acknowledging that the donor no longer retains or uses that income, it lowers the net cost of giving. For someone in the 37% tax bracket, a $100,000 donation effectively costs them $63,000 after income, not because the government “pays” $37,000 to the Met, but because the donor voluntarily allocates $100,000 of their income to a public charity, the government recognizes this contribution, and the donor’s income taxes are reduced accordingly.

The deduction is neutral regarding the cause; it applies equally to donations to both food banks and fashion museums, small-town PTAs, and major universities. If elite institutions receive more funding, it reflects donor preferences and wealth concentration—not tax code favoritism.

The True Motivation Behind Charitable Giving Isn’t a Tax Deduction

Experienced advisors understand that most gifts, large or small, are not motivated by deductions. Donors give support to causes they believe in, to preserve their legacy, or to create intergenerational meaning. The tax benefit might influence the structure or size of a gift, but not its existence.

Consider a client of mine, an elderly woman with no family and a modest estate. Her assets were well below the federal estate tax exemption, and after the 2017 tax reforms, she no longer itemized deductions. Nonetheless, she gave generously during her lifetime and structured her estate so that 100% of her assets went to local grassroot charities reflecting her values. Her decision was driven by impact, not taxes.

This pattern aligns with national data. After the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act raised the standard deduction and lowered marginal rates—reducing federal incentives to donate—charitable giving only fell by about 4%. If charitable giving is motivated by tax deductions, it would have fallen by a much greater percentage. Most Americans donate to charities because they support their mission, not for tax benefits.

Charitable Vehicles Like CRTs and DAFs Are Tools, Not Loopholes

Appelbaum’s critique, like many others, wrongly portrays advanced charitable vehicles, such as charitable remainder trusts (CRTs), charitable lead annuity trusts (CLATs), and donor-advised funds (DAFs), as tax shelters for the wealthy. This is misleading.

Each tool includes built-in charitable requirements. A CRT must deliver at least 10% of its value to charity. A CLAT can reduce estate taxes, but only if substantial payments, sometimes equaling or exceeding the transferred amount, go to nonprofits first. A DAF requires irrevocable contributions to a sponsoring charity, and while donors retain advisory privileges, the charity is not obligated to follow the donor’s advice, and assets can never revert to private hands.

These strategies align wealth management with public benefit, allowing donors to manage lifetime income, reduce capital gains, and still make a significant impact. Far from undermining philanthropy, they are essential tools for magnifying impact, especially when integrated with values-based planning.

A Better Conversation: From Tax Minimization to Impact Maximization

To improve the tax code, the discussion should focus on increasing access to deductions by reinstating above-the-line deductions or creating credits for lower-income donors, rather than eliminating incentives that drive billions in annual giving.

For estate planners, CPAs, and financial advisors, the key takeaway is that tax tools should serve philanthropic intent, not drive it. Start planning conversations with the “why” of giving. Use vehicles like CRTs, CLATs, and DAFs not just for tax efficiency, but to foster legacy, continuity, and family engagement.

Whether the gift is to the Met or a neighborhood shelter, effective charitable planning ensures that wealth becomes a tool for enduring social good. That’s a message far more enduring than any red-carpet headline.

Read the full article here