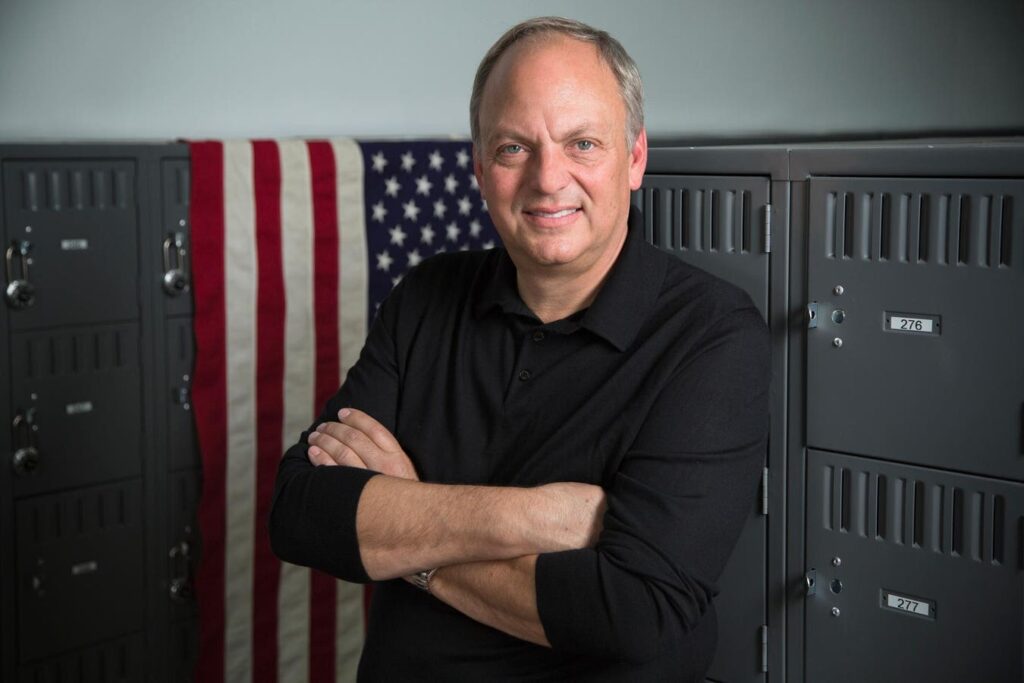

While one billionaire’s lawsuit seeking damages in the Charles Littlejohn tax leak matter was cut short, another rich victim is taking a different tack: suing Littlejohn’s employer. David MacNeil, the founder and owner of WeatherTech, has filed a lawsuit against Booz Allen, claiming that the company failed to safeguard its computer systems and protect Internal Revenue Service networks and databases, resulting in the exposure of the confidential tax return information of thousands of American taxpayers—including him. He is seeking damages, alleging that the leak has caused him, among other things, reputational harm.

Booz Allen, a management and technology consulting firm headquartered in MacLean, Virginia, has a long history of working with US civilian and defense agencies, including the IRS, resulting in billions of government-funded contract dollars. The company employs about 36,000 people—and one of those employees used to be Charles Littlejohn.

Access to taxpayer data is tightly restricted by law—a protection that’s been in the news recently because of demands by Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to access that data.

Charles Littlejohn

Charles Littlejohn is a former IRS contractor—employed through Booz Allen—who went to prison in 2024 for disclosing thousands of tax returns, including Donald Trump’s—without authorization.

From 2018 to 2020, Littlejohn stole tax returns and return information associated with Donald Trump. According to prosecutors, Littlejohn viewed Trump as “dangerous and a threat to democracy” and had intended to provide private tax information to the public. (Trump was not initially named in court documents but this information was confirmed in Littlejohn’s sentencing memorandum.)

Littlejohn initially disclosed Trump’s tax information to the New York Times. He didn’t stop there. According to court records in Littlejohn’s criminal case, he turned over returns and return information dating back more than 15 years for billionaires Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, and Michael Bloomberg to ProPublica. The data contained not only tax returns but also investments, stock trades, gambling winnings, audit determinations, and many other types of financial material. But it wasn’t only those wealthy individuals who were impacted—it appears that some taxpayers who were shareholders in passthrough entities were also affected (in other words, their information appeared on Forms K-1 or the equivalent from passthrough entities that had their information leaked).

MacNeil figured prominently in a 2021 story published by ProPublica describing how the 2017 Trump tax cuts encouraged CEOs who own passthrough companies to save on taxes by reducing their own salaries and taking more of their earnings in company profits. According to ProPublica, MacNeil’s WeatherTech salary fell from $68 million in 2017 to $47 million in 2018 and $17 million in 2019. Meanwhile, ProPublica reported, his company’s profits climbed, saving him an estimated $8 million in tax during the first two years of the Trump tax cuts, which where effective in 2018. MacNeil, whose advertising touts the fact that his products are made in America, told ProPublica that he used any tax savings to create more jobs: “You want me investing in my country — my fellow Americans? Get out of my pocket.”

Littlejohn accessed the returns on an IRS database after using broad search parameters designed to conceal the true purpose of his queries. He then evaded IRS protocols established to detect and prevent large downloads or uploads from IRS devices or systems before saving the tax returns to multiple personal storage devices, including an iPod.

In October of 2023, Littlejohn pleaded guilty to unauthorized disclosure of tax returns and return information—a violation of section 7213(a)(1) of the tax code, the most serious offense for leaking tax information. Littlejohn was sentenced to the maximum penalty of five years—he is currently serving his sentence in a Florida prison.

Lawsuit Against IRS

In 2022, billionaire Kenneth C. Griffin, the founder and CEO of Miami-based hedge fund Citadel, filed suit against the IRS for “their willful and intentional failure to establish appropriate administrative, technical, and/or physical safeguards over its records system to insure the security and confidentiality of Mr. Griffin’s confidential tax return information.”

Griffin’s information was included in the data leaked to ProPublica, the nonprofit investigative news organization, and he filed suit months before Littlejohn was revealed to be the leaker. Under section 7431(a), victims may be able to sue for damages for the unauthorized inspection or disclosure of their tax information. If the accused person is an officer or employee of the United States, the taxpayer may sue the United States in district court. If the accused person is not an officer or employee of the United States, the taxpayer may sue the individual.

Once the information about Littlejohn was made public, Griffin amended his complaint, but the IRS argued for dismissal, noting, “Since Littlejohn was not an officer or employee of the IRS, Mr. Griffin’s claim for damages in Count I lies not against the United States (as pleaded) under § 7431(a)(1), but rather against Littlejohn under § 7431(a)(2).”

In other words, since Littlejohn was a contractor—and not an employee—of the federal government, the IRS said that Griffin wasn’t entitled to recovery under the statute from the government, just Littlejohn (who has limited resources, according to court documents). The court seemed to agree, but allowed the lawsuit to proceed. Eventually, Griffin settled the lawsuit, resulting in, among other things, an apology from the IRS. (Other than the apology, the terms of the settlement were not made public.)

MacNeil didn’t try that theory, instead suing Littlejohn’s employer, Booz Allen. Booz Allen didn’t offer comment for this story instead referring to a 2024 statement on its website which called Littlejohn’s actions “those of a rogue actor hiding his misconduct on government systems.”

Booz Allen Lawsuit

MacNeil’s lawsuit alleges that Booz Allen “willingly allowed its employees unrestricted and unmonitored access to IRS databases and systems.” That made it easy, the lawsuit says, for Littlejohn to retrieve personally identifiable taxpayer data and to download that data, which was provided to the New York Times and ProPublica. The data was used in articles about MacNeil which, according to the lawsuit, provided a “highly misleading characterization of his tax return history.” The result, MacNeil’s lawyers argue, has been “ongoing injury including, but not limited to, public backlash, significant reputational harm, and loss of privacy, and economic damages.”

The IRS notified MacNeil about the breach in late 2023 (the IRS notified more taxpayers in early 2024). The IRS is required, by law, to give notice to any other victims of the breach it can identify, even if their names were never published.

That notice landed in mailboxes as Letter 6613-A, IRC 7431(e) Notification Letter. In this case, Letter 6613-A indicated that an IRS contractor has been charged with the unauthorized disclosure or inspection of the taxpayer’s tax return or return information. The letter indicated that an IRS independent contractor—not named in the letter but clearly referencing Littlejohn—was charged with the unauthorized disclosure of the taxpayer’s information between 2018 and 2020.

On February 14, 2025, the IRS disclosed to the House Judiciary Committee that it had “mailed notifications to 405,427 taxpayers whose taxpayer information was inappropriately disclosed by Mr. Littlejohn” and that ’89 [percent] of the[se] taxpayers are business entities.” Earlier this month, the Committee sent a letter requesting that Littlejohn appear before it to testify.

Prior Security Issues

The lawsuit argues that this isn’t Booz Allen’s first run-in with security issues. In July 2011, the suit notes, Booz Allen admitted that the hacking group “Anonymous” had infiltrated its company network and stolen a list of approximately 90,000 military email addresses and encrypted passwords.

But that wasn’t Booz Allen’s most infamous breach. In 2013, another then-Booz Allen employee, Edward Snowden, used his Booz Allen credentials and access to download thousands of top-secret security documents. Snowden leaked the classified materials to multiple journalists, disclosing national secrets and severely compromising the NSA’s anti-terror surveillance program. As noted in the lawsuit, Snowden ultimately fled to Russia, where Vladimir Putin granted him citizenship in 2022.

In 2016, authorities arrested then-Booz Allen computer analyst Harold Martin for stealing approximately 50 terabytes of confidential data from the NSA, in a breach that authorities have called the “largest theft of classified information in U.S. history.” The information included personal details of government employees and “Top Secret” email chains, handwritten notes describing the NSA’s classified computer infrastructure, and descriptions of classified technical operations. Martin ultimately pleaded guilty to stealing classified information.

Those, along with other examples of breaches outlined in the lawsuit, were characterized as “pervasive data security failures and unethical practices” which, the lawsuit says, “culminated in an unprecedented taxpayer data breach” by Littlejohn. As Littlejohn’s employer, Booz Allen, the lawsuit alleges, had control over Littlejohn’s schedule and credentials—notably, those were issues that the IRS argued in the Griffin suit made the tax agency not liable for the breach.

The human impact of Littlejohn’s crimes and Booz Allen’s misconduct, MacNeil argues, is enormous. As a result, he is seeking damages in a lawsuit filed on March 24, 2025, in the U.S. District Court in Maryland, Southern Division. MacNeil is represented by Miles & Stockbridge, P.C., in Baltimore, Maryland. A request for comment made to the attorneys of record for MacNeil earlier this morning was not returned.

Read the full article here