It turns out that all of those “no” votes in committee didn’t amount to much once the tax bill hit the House floor on Thursday morning.

House Republicans passed the “big, beautiful tax bill” with a 215-214 vote. Only two Republicans, Warren Davidson (Ohio) and Thomas Massie (Ky.) voted “no” on the grounds that the bill would add significantly to federal deficits—two others, Andrew Garbarino (N.Y. and David Schweikert (Ariz.) didn’t vote, while Andy Harris (Md.) voted “present.” The tax portion of the bill before any changes were made, would cost $3.7 trillion over the next decade, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).

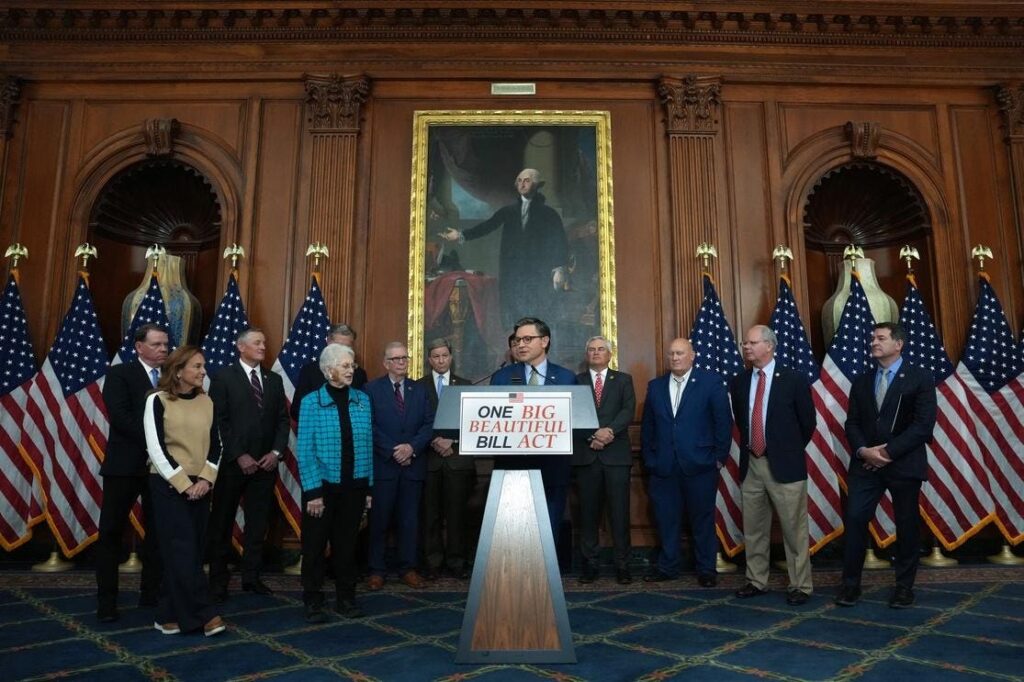

House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) had hoped to get the bill to the finish line in the House before the Memorial Day break, which starts tomorrow. But first, he would have to woo votes from Republicans unhappy with, among other things, the limits on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and the delay in new work requirements for Medicaid, in addition to the overall cost of the package. Following some tweaks, the House voted on the package without knowing the final cost, a fact that Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas) touched on, saying, “The deficit hawks have become chicken hawks tonight, in submission to Trump, the self-described king of debt.”

Key Differences

Johnson worked out some details with House Republicans to ensure a yes vote. You can read about the earlier version here.

Following is a look at some of the changes from the early version to the most recent version:

State and Local Tax Deduction

Currently, if you itemize your deductions, you can deduct state and local income taxes or sales taxes and state and local property taxes—but only up to a $10,000 cap for all these taxes combined. This is often referred to as the SALT cap. Without any action at all, the SALT cap would expire—before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), Trump’s big 2017 tax cut, there was no cap on the SALT deduction, other than the Pease limitations, which generally limits deductions for high-income taxpayers.

The $10,000 cap was a sore spot for many taxpayers in high tax states. The latest version of the bill raises the cap to $40,000 per household (the previous version had lifted the cap to $15,000 for singles and $30,000 for married couples filing jointly and some Republicans in the House had hoped to see it boosted to $60,000). The income phaseout—the point at which the value of the tax deduction would decrease as income increases—will begin at $500,000, instead of $400,000 in the previous bill. (For married taxpayers filing separately, the new deduction cap would be $20,000 and the income phaseout would begin at $250,000.) The cap and income phaseout would be subject to automatic annual increases of 1%.

Medicaid

Medicaid, the program that provides health insurance to more than 71 million lower-income Americans, would be significantly impacted by the bill. Chief among the changes? New work requirements. In the earlier version, this was slated to kick in once President Trump left office. The new work requirements would begin in December 2026 under the latest House bill.

Experts predict that changes to Medicaid will save $625 billion at the federal level (although some of those costs could be transferred to states). They also estimate that between 8.6 and 14 million Americans could lose health insurance over the next decade.

Green Credits

The most conservative Republicans weren’t happy with the speed at which the old version of the bill would have eliminated green credits previously available under the Biden era Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—they wanted them gone faster. The new version of the bill now also shrinks the phaseout window for some existing tax credits for low-carbon electricity—to claim the credit, building solar-, wind-, geothermal- or battery-powered plants must begin construction within 60 days of the bill being signed into law.

Debt Ceiling

The final version of the House bill retains a $4 trillion debt ceiling hike, which fiscal conservatives may oppose.

Market Reactions

U.S. stock markets opened lower as the tax bill continued to make investors nervous. Here’s why. As federal deficits rise, investors start shuffling their allocations. Bond yields—the income you earn from bonds—tend to go up with risky behavior. That’s because investors want more incentives to buy since the chances of default are higher. (That, in turn, can impact consumer rates, like your mortgage.) As investors chase those higher yields, they may shift money from stocks to bonds. That reduces demand for stocks, which can send prices lower.

Complicating matters even further, last week, Moody’s lowered the U.S. credit score from a Aaa (prime) to Aa1 (high grade). Moody noting, “Over the next decade, we expect larger deficits as entitlement spending rises while government revenue remains broadly flat. In turn, persistent, large fiscal deficits will drive the government’s debt and interest burden higher. The US’ fiscal performance is likely to deteriorate relative to its own past and compared to other highly-rated sovereigns.”

What’s Next

The bill is likely to face opposition in the business-friendly Senate, which may seek to add or extend business-related tax breaks, potentially increasing the cost unless additional cuts are made elsewhere.

Additionally, any version approved by the Senate must match exactly the language in the House bill. For example, the Senate version of the just passed “no tax on tips” bill had key differences from the House version. Those issues must be resolved before the bill can become law.

(Note: This is a developing story. Keep checking our coverage for more details.)

Read the full article here