Low-income workers who leave their jobs or reduce their hours to care for frail parents or spouses risk losing their own Medicaid benefits, according to a House committee’s budget plan. At the same time, major cuts in projected federal Medicaid funding threaten the ability of states to continue to provide services to low-income seniors and younger people with disabilities.

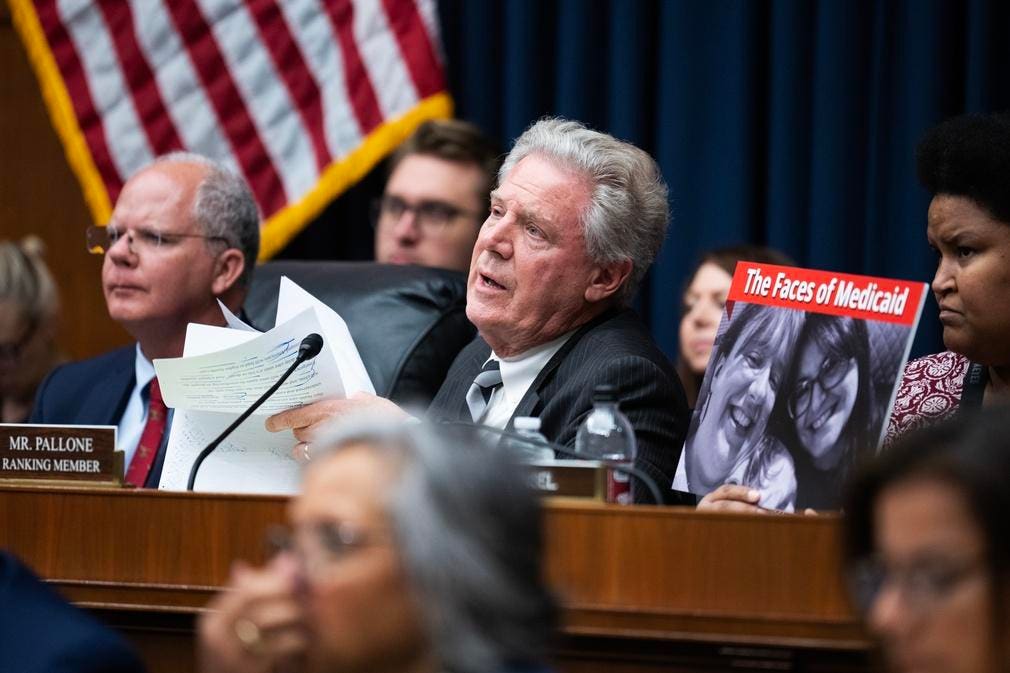

Older adults and their families could be profoundly affected by two major Medicaid changes in the section of the House budget approved by the Energy and Commerce Committee on May 14.

The first would require states to bar Medicaid coverage for people who don’t work at least 80 hours a month at paid jobs, perform community service, or are at least half-time students.

The committee bill also would reduce the projected federal share of Medicaid by more than $600 billion over the next decade, though many of its proposed changes would not take effect for several years. Much of that savings would come from direct cuts in federal payments for the program. And some would come from the new work requirement, which would reduce the number of people eligible for Medicaid.

The Medicaid provisions will be combined with other spending and tax changes in a single 2026 budget plan. House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) hopes the full House will vote on the entire fiscal package by Memorial Day. The Senate will try to pass its own version later this year.

What Medicaid Does

Medicaid provides health and long-term care for low-income people of all ages. While the program is operated by the states, the federal government funds about 70% of the costs. The amount varies widely by state.

Medicaid spends more than half its budget on medical and long-term care for frail, low-income older adults and younger people with disabilities, according to a KFF data note. And Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data shows about one-quarter of all Medicaid benefits, more than $200 billion annually, pays for long-term care for about 9 million frail older adults and younger people with disabilities.

The Work Requirement

People who have a disability or are older than age 64 would be exempt from the work requirement, which is not scheduled to take effect until 2029. But what about those caring for frail parents? Does it mean a low-income worker who gives up a job to care for mom would lose Medicaid benefits? It might.

The bill includes an exception for “the parent, guardian, or caretaker relative of a disabled individual or a dependent child” but is silent on whether those caring for seniors also would have to work at a paid job.

Of course, the vast majority of those caring for older adults are not parents or guardians. “Caretaker relative” is common in Medicaid law. But it applies to those caring for a dependent child, not a parent, spouse, or sibling.

And that puts those assisting parents at risk of losing their Medicaid benefits.

Even if caregiving for older adults eventually is protected, the bill still leaves unresolved many questions, such as:

- If two low-income adult children are caring for a parent, could they both claim the exemption and remain on Medicaid? Or could only one? And what standard would apply?

- What level of disability or what conditions will be sufficient to trigger an exemption?

- What about family caregivers who are paid to care for relatives, which Medicaid does in several states? Would that be considered work for the purposes of the bill?

The bill leaves answers to all these questions up to the Department of Health and Human Services, which must clarify the work requirement by 2027.

Federal Funding Cuts

More broadly, the committee says the bill reduces planned federal Medicaid spending by $625 billion through 2034, though it likely would cut it by much more.

The biggest change is highly technical, but important. Currently, nearly every state imposes a tax on the hospitals and nursing homes that care for Medicaid beneficiaries. In a complex set of transactions, the states effectively increase their payments to those providers by the amount of the tax. But because most of that higher state payment is picked up by the feds, both the states and the providers come out ahead.

The big unanswered question is how would the states respond to losing hundreds of billions in federal dollars?

They could raise taxes to replace the lost federal dollars, though that seems improbable in the current political climate. Some may do nothing, hoping the law changes before the cuts take effect.

Many would likely shrink their Medicaid programs, either by reducing payments to nursing homes, home care agencies, and hospitals; cutting benefits; or limiting eligibility.

One big fear: States are required by federal law to provide long-term care in nursing homes. But home care is an optional benefit, which states could more easily trim, even though that is where most people want to live.

While Congress appears to be paying little attention to the impact of the proposed Medicaid changes on older adults, people with disabilities, and their families, the consequences could be profound.

Read the full article here